The Logic of Bad IPv6 Address Management

What Makes Sense for IPv4 Doesn't Make Sense for IPv6

This blog is an updated version of an article I published in Network World on 10/3/2012

I’ve written about IPv6 address design previously, and in that post I briefly touched on the fact that our long-ingrained habits of IPv4 address design can lead us astray when working with IPv6. I’d like to revisit that topic, with an eye to both design and management.

To recap: IPv4 address design and management is all about conservation. IPv4 address supplies have been slowly diminishing for the past three decades, so we’re very careful with our supply. When you go to your allocation authority – whether that is the address administrator within your organization, your service provider, or your Regional Internet Registry (RIR) – to ask for more IPv4 addresses, you are required to provide compelling justification for why you need a bit of their limited resource. Here in 2020, it might not matter how convincing your justification is — the allocation authority might not have any IPv4 space left to give you. When you create your IPv4 addressing schema, you design for individual subnets, using VLSM to carefully allocate your precious resource so that you (hopefully) have the right balance between enough subnets in your network and enough hosts on each subnet. The idea of consistently assigning, say, a /24 or a /20 to every single IPv4 subnet regardless of the number of hosts on that subnet is, for very many network engineers, unthinkable.

The conservative instinct runs deep in anyone who has worked with IPv4 for a while, but this instinct can lead you into some poor decisions when working with IPv6. There is one overarching rule I tell all my clients when beginning an IPv6 address design:

Forget everything you ever learned about IPv4 address design

Maybe that sounds a little overheated, but the fact is that every bad decision I ‘ve seen made in IPv6 addressing can be traced to IPv4 conservatism.

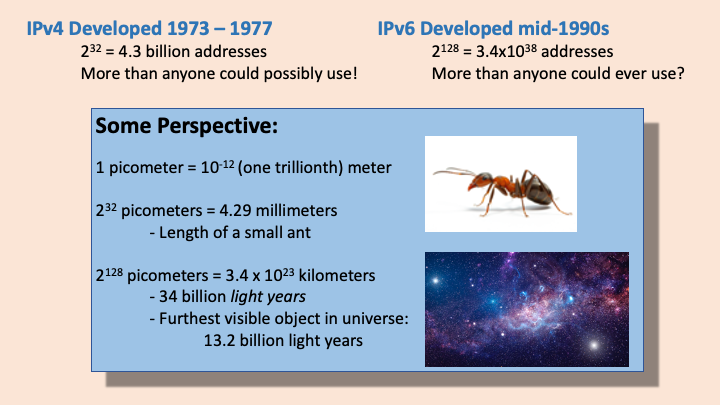

IPv6 is a vast resource, vast at a scale that most of us have a hard time envisioning. Those of us who speak regularly about IPv6 to customers or in public forums have our favorite analogies to try to convey the unimaginable differences in size – mine involves ants and light years – because it’s important to get across that we simply are not going to run out of IPv6 addresses.

Go Ahead. Waste a Few Million Trillion Addresses. There’s Always More.

The IPv4 influence on IPv6 thinking most often shows its influence when talking about addressing point-to-point links. The IANA and all the RIRs recommend using /64 subnets everywhere in your network, including on point-to-point links. But so many designers just can’t bring themselves to do it. The reasoning goes like this:

“A /64 subnet is 264 addresses. That’s about 18 million trillion addresses, and you want me to use just two of them and waste all the rest? That’s just crazy!”

Okay, but you have no problem using /64 subnets on regular LANs or VLANs. How many hosts will you put on one of those subnets? 500? 1000? Let’s say 1000.

When you’re talking about18 million trillion addresses, the difference between 2 and 1000 is negligible. So why is 264 – 2 horrifyingly wasteful, while 264 – 1000 is reasonable?

If you’re worried about using up your allocation of IPv6 addresses, stop it. If your allocation does not support addressing every subnet in your network as a /64 – including point-to-point links – the problem is not that you are managing your addressing frivolously. The problem is that your allocation isn’t large enough. Go ask your addressing authority for more. Remember, RIR and IANA practices encourage you to use /64 everywhere. They will give you enough space to do that.

Confessions of an IPv4 Conservative

The other area in which I’ve seen IPv4 thinking influence IPv6 addressing is on the prefix allocation side. And I have a confession to make: Until recently I’ve been guilty of this wrongheaded thinking myself.

As a consultant primarily to service providers, I have frequently stated that “common industry practice” when allocating IPv6 blocks to customers is to use one of three assignment classes:

- Large customers get a /48 prefix. That gives them 65,536 /64 subnets.

- Medium customers get a /56 prefix. That gives them 256 /64 subnets.

- Small customers (meaning home or small office customers) get a single /64 prefix. A concern with this last class is that future applications might require subnets even in a home or small office, so a hedge would be to assign /60 prefixes, allowing 16 /64 subnets.

Here’s the problem with that practice:

How do you define large, medium, and small? You could say the dividing line is subnet requirements, but how are your skills at predicting the future? What happens if a customer grows from your definition of medium to your definition of large? Do you re-allocate and make them re-address their network? That’s a complicated project. It sounds like a potential customer relations problem.

For that matter, why is it any of your business to decide what size of networks your customers have?

Just as you should be using /64s on every subnet, why not allocate a /48 prefix to every customer site? In general a site should be a building. So if your customer occupies a single building, give them a /48 no matter how small the building is. If your customer has a campus with 30 buildings, give them 30 /48s. If your customer has 300 branch offices in your service area, give them 300 /48s.

Using a /48 as the unit of site allocation helps you avoid another imprecision, the “very large customer.” It’s used to mean a customer that needs an address pool larger than a /48: a /47 prefix or shorter. Presumably such a customer has multiple sites, so a /48 per site gives you a reasonably well-defined allocation guide.

Maybe a customer occupies a single very large building, and wants more than one /48. Give them what they want. Let them decide their needs, rather than trying to pigeonhole them into some arbitrary class.

And, yes, a house is a site. An apartment is a site. If you are serving residential customers, give each of them a /48.

Maybe with that last recommendation you decide to put your foot down. “A /48 for a residential user?” you say. “That’s ridiculous! No home user is ever going to have 65 thousand subnets! No small office is ever going to have 65 thousand subnets!”

I think you’re right. They’ll never use 65,536 subnets. But how do you know that a /60 assignment providing 16 subnets is enough? In the home of the future maybe entertainment systems, security systems, communications systems, appliances, environmental and power controls, and medical monitors are all on separate subnets. Maybe each member of the house has a set of all these subnets dedicated just to him or her. Real multitenancy! And these are just the services we have presently. What about all those we cannot foresee? 16 subnets are certainly not enough, but 65K should cover any eventuality.

How many subnets the household or small office of the future needs, or whether it will ever need more than one, is not really your problem. Worrying about wasting most of the 65,536 /64 subnets in a /48 prefix is the same as worrying about wasting most of 18 million trillion addresses on a single /64 subnet.

Waste is not the point, because with IPv6 address conservation becomes irrelevant in practical designs. What is important is consistency. Just as all subnets in a network should be /64, all prefixes assigned by an address management authority should be a /48 or some multiple of /48. You should only assign a /64 in the corner case where you know for sure that subnetting will never, ever be needed. Homes and small offices do not meet that criterion.

/48 or /56?

And that brings us to that mid-sized allocation of /56. It imposes an arbitrary and hard-to-define boundary for businesses, but what about residences and small offices? While the 16 subnets you get with a /60 might not be enough for future subnetting needs, surely the 256 subnets you get with a /56 is enough.

But do you know for sure? What are the conditions for deciding that? In my opinion, it’s better to assign a /48 to residential users and have assurance that they will have far more subnet capability than they can ever use. Again, we can do this with IPv6 because we have the capacity.

This isn’t a new idea at all. In fact it is an old idea. Public policy has declared it obsolete, but is it obsolete for a good reason?

RFC 3177, authored by the Internet Architecture Board (IAB) and the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG), explicitly recommended:

“Home network subscribers, connecting through on-demand or always-on connections should receive a /48.”

But RFC 6177 obsoleted RFC 3177 in March of l2011. One of the main focuses of this newer RFC was to move away from a one-size-fits-all prefix allocation, particularly in regards to home users. Specifically, it states, “End sites come in different shapes and sizes, and a one-size-fits-all approach is not necessary or appropriate.” It goes on to say, “While the /48 recommendation does simplify address space management for end sites, it has also been widely criticized as being wasteful.”

There’s that word again. Wasteful.

RFC 6177 was met with relief by many service provider engineers worried that the default /48 end site size was wildly extravagant. And it reflected policy changes already made by the RIRs, in which /56 allocations to SOHO users are encouraged. RIRs also changed their default end site assignment size (for the purposes of utilization calculation) to /56, and their HD-ratio from 0.8 to 0.94. This is all based on a well-reasoned presentation by Geoff Huston to RIPE 50 in May of 2005, and according to his calculations the policy changes should extend the useful lifetime of IPv6 from an estimated 60 years to an estimated 100 years.

Nevertheless, all this is based on a speculation that 256 subnets will most likely be more than sufficient for SOHO users. I readily agree that it probably is. In fact saying that somewhere out there in the future, maybe 25 or 30 years down the road, our home networks might – maybe – run some combination of applications (we don’t know what they are!) that might – maybe – drive subnet needs above 256, is much more speculative.

But that’s not the point.

The point is that imposing boundaries – whether they are very large vs large vs medium vs small or enterprise vs SOHO users – is based on a compulsion to be cautious with IPv6 as a resource.

Are You Ready for IPv7?

When I talk to customers or interest groups about IPv6 address design, I’m inevitably asked the question, “So twenty years from now, are we going to again be in an uproar, deploying IPv7 because we’ve run out of IPv6 addresses?”

My calculations are much more back-of-the-envelope than Geoff’s, but let’s look at what we have available to us. Currently the first three bits of all IPv6 global unicast addresses are 001. That gives us 245 or roughly 35 trillion /48 prefixes. Right now, the world population is right at 7 billion people. So the current IPv6 global uncast address space is enough for every man, woman, and child on the planet to have 5,000 /48 prefixes.

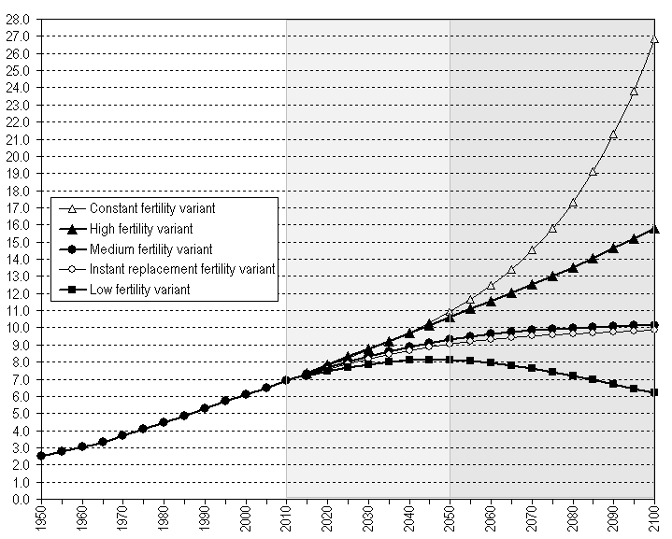

By 2100, the UN projects a world population of 10 billion. That’s actually a median figure; should current population growth continue at present rates, it could be as high as 16 billion by 2100. For our exercise, let’s take that extreme (although if that level of growth comes about, we will have much worse problems than whether there are enough IP addresses to go around). Using the current global unicast supply, that’s still 2200 /48 prefixes for each of those 16 billion people.

Remember, too, that these figures are based on the current allocation of IPv6 global unicast addresses; all prefixes that start with 001. That’s an eighth of the total IPv6 address space. Right now, 85% of the IPv6 address space is held in reserve. The other prefixes currently being used start with 111: Things like multicast, ULAs, and link-local addresses. Let’s be generous and say that all prefixes starting with 111 get set aside for non-global or non-unicast addresses. There are also the unspecified address (0/128) and the loopback address (::1/128), but they are negligible out of the 000 prefixes. That leaves us, should all those 001 global unicast prefixes prove insufficient, with three quarters of the remaining IPv6 address space to expand into.

IP is more likely to become obsolete before we run out of IPv6 addresses.

I’m not advocating here that the RIRs go back to using a /48 as their only unit of site allocation. That ship has sailed, and they’re not going to confuse the industry by changing their policies again. I am advocating that you forget about /127s and use /64 subnets throughout your network, including point-to-point links. I’m also advocating that if you’re a service provider or an address manager in an organization, at least consider using /48s as your single unit of site allocation, and simplify your life.

Most importantly, what I hope you take away from all this is a healthy appreciation for the scale of the IPv6 address space and that if you’re worried about waste, you’re probably thinking too small.