Measuring the Unmeasurable

05/20/2020 Category: Network Design

I’ve been an avid skier for more most of my life. When we get our first light October snowfalls here in Colorado, I start getting serious about getting in shape. Sadly, over the past few years job demands have been such that I haven’t been able to give much attention to skiing. I’ve fallen into a perpetual cycle of missing a ski season, getting out of shape from not skiing, missing another season because I’m out of shape, getting further out of shape… You get it.

Given the state of the economy it's certainly good to be employed and busy, but watching the Colorado ski resorts close, without having gotten up there yet again this season, is downright depressing.

“Well good for you,” you may say, “but what does any of that have to do with networking?”

There are three things skiers practice that network architects also practice:

- Risk assessment;

- Increasing confidence; and

- Reducing uncertainty

At the top of any ungroomed slope I do a quick risk assessment: The angle of the slope, bumps, the likelihood of hidden obstacles, the condition of the snow, the quality of the light. Whether I’m warmed up or worn out.

Something could still go wrong, but my risk assessment reduces uncertainty enough that if I decide to ski the run I have an acceptable level of confidence that I will arrive at the bottom of the run unhurt and unembarrassed.

I said a couple of important things, in that last sentence, about risk assessment: I reduce uncertainty and I increase confidence.

Risk is inversely proportional to uncertainty. If something is 100% certain, there is 0% risk. If you have absolutely no idea of an outcome (0% certainty), then you are looking at 100% risk.

In my previous post I contrasted a count, which gives you an exact number, with a measurement, which is an approximation. In other words, a measurement is a reduction in uncertainty. Not an elimination of uncertainty (and this is an important point!), but a reduction in uncertainty. The more accurate we can make the approximation, the more uncertainty we eliminate. But there is some point, as I emphasized in the previous post, at which a more accurate approximation becomes unnecessary and perhaps unjustifiably expensive.

One of the questions I asked at the end of that post is, “How do we measure things that we might think of as intangibles, such as risk and security?” The first step, which seems obvious but in practice is often overlooked, is to define the “intangible” as precisely as possible within the context that we plan to use it. The question is simple: What do you mean by “risk?” What do you mean by “security?” What do you mean by “quality?” What do you mean by “performance?”

The answer is not so simple. Or at least it shouldn’t be. You and your project team could – and should – spend one or several meetings just coming up with the answer to “What do we mean by…?” It’s an exercise that puts specifics around a fuzzy concept, and what you will find is that as you reduce ambiguity, you begin realizing that most of those specifics are measurable.

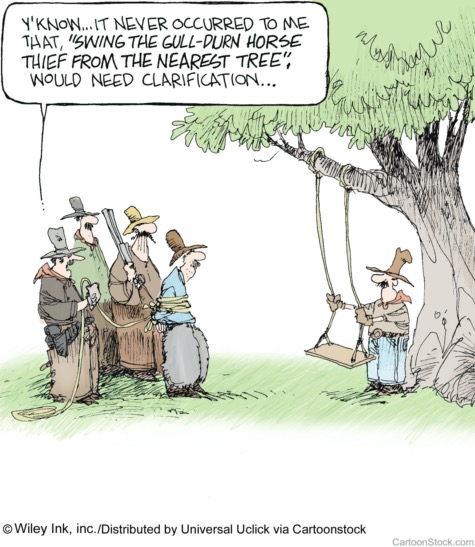

Douglas Hubbard defines this exercise as a clarification chain:

- If something is better or worse, then it is different in some relevant way.

- Differences are observable.

- If it is observable, it can be detected as an amount or range of possible amounts.

- If it can be detected as a range of possible amounts, it can be measured.

Here’s an example. How often have you heard the term “network agility?” Probably pretty close to the number of times you’ve listened to product pitches over the past five or so years, right? It’s a species of intangible commonly known as marketing fluff. We usually understand it to mean something like “the ability of the network to quickly adapt to change.”

Okay, how do we quantify “quickly” as a difference between what we have and what the product will do for us? Days versus weeks? Hours versus days? Seconds versus hours?

What does “adapt” mean? Does it mean the network can continue meeting certain performance benchmarks under variable application demands? What are those benchmarks? What are the characteristics of the variable application demands? Notice that digging a little deeper gets us closer to things that can be measured.

And what does “change” mean? Network anomalies? What kind of anomalies? Does it mean adding and modifying a virtualization overlays like VXLAN or SD-WAN? Does it mean a new kind of security threat?

Asking progressively more detailed questions about how a product might improve the agility of your particular network can help you (assuming you see potential business value) design and run a proof of concept trial with specific expectations defining success. The PoC results, in turn, give you the data you need to go into the boardroom and answer the pointed business questions of “What are the benefits?” and “What are the risks?”

But you’re going to be asked an even more difficult question: What is your confidence level that your benefit and risk projections are correct?

What the heck is a confidence level, and how do you determine it? Or as I asked it in my previous post, how do we know a measurement is close enough? I’ll address that in my next post.

In the meantime, I’ve promised myself that this past season – cut short by coronavirus concerns – will be the last season that I don’t get my skis on. A Colorado winter is a terrible thing to waste, so I’ve got some knee exercises to get to.